|

|

Science and Faith

Science and faith. Where is the common ground? Do you find inspiration from science for exploring faith traditions? Do you find support for scientific thinking from the history of faith and religious writings?

There are thousands of years of religious narrative about the relationship between faith and a spirit of curiosity, creativity and scientific inquiry. At their best, religious writings provide freedom to ask "why" and "how" and to explore the meaning of things. Songs of praise point to the complexity of creation and the knowledge to be found there. And even the many "miracles of abundance" -- the loaves and fishes, manna from heaven, water from a rock, an abundant catch of fish, water into wine, parables about sowing and harvests -- show a respect for the potential of the natural world.

A new acquaintance recently challenged me about the relationship between science and faith. Many things were troubling him about the history of Christianity, from the role of Constantine to political controversies today. But most of all, "What about the way the church treated Galileo?" he asked.

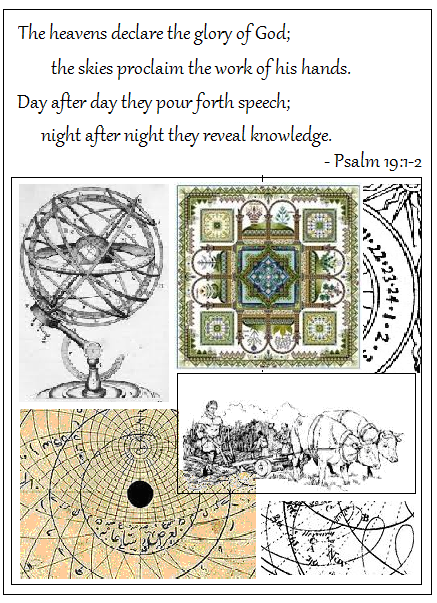

During much of the middle ages, the study of astronomy, agriculture, engineering, mathematics, music and the arts advanced through an exchange of ideas among Arabs, Persians, Christians and others. Faith and science were natural allies during this period of quiet growth in technology and science.

Some historians suggest that it was only later, during the Renaissance, that a rising merchant and intellectual class characterized the past centuries as "the dark ages" and began to stake out a tension between modernity and backwardness; and between science and religion.

Meanwhile, many religious leaders were threatened by the fast pace of change in society and began to narrow their views of the world, often rejecting science and giving root to modern tensions between faith and science.

There would be a back-and-forth between times of openness and times of narrowness in religious thought in the following centuries. Times of social stress might result in narrow thinking; but eventually there would be a revival of a spirit of openness and inquiry.

The foundations of openness and inquiry go far back to the early roots of the church. For example, St. Augustine of Hippo, a bishop in North Africa during the early fifth century (354 AD to 430 AD), warned against narrowness of thinking. Throughout a commentary titled "The Literal Meaning of Genesis" he explores the possible meanings of the creation texts and advises that science will advance; and the concept of God as the origin of time and matter will become clearer and clearer as scientific knowledge moves forward.

Many of the psalms about creation celebrate a spirit of inquiry, offering poetic images of creation and a sense of wonder. In Psalm 19, the writer celebrates a sense of wonder:

The heavens declare the glory of God;

the skies proclaim the work of his hands.

Day after day they pour forth speech;

night after night they reveal knowledge.

They have no speech, they use no words;

no sound is heard from them.

Yet their voice goes out into all the earth,

their words to the ends of the world.

How can the contemporary church revive a spirit of inquiry and openness?

Many elements of church teaching reflect the goals, hopes and worries of an older generation for a younger generation.

For example, in the centuries before the Renaissance, many Christians turned their attention to the sciences and technology, both for the practical benefits of developing and discovering technology for agriculture and production, for applications to architecture and art, for the study of medicine, and for the more abstract benefits of intellectual inquiry. Whenever possible, families would seek opportunities for education for their children, through the church, universities, apprenticeships or other structures.

In contrast, narrowness of thinking emerges in conditions of social stress. For example, an era of strict discipline and teaching in churches and at in homes and schools reflects the worries of generations who face discrimination and danger in the wider world; with the sense that strictness and discipline can help to inoculate children against the greater dangers to be faced in the world. Or, for example, an era that emphasizes orthodox thought over freedom of thought reflects the worries of a generation who feel that their faith community is greatly outnumbered and endangered.

A spirit of inquiry and openness emerges in a generation that feels that they, and their children, will be able to thrive in the wider world, and that their faith traditions and values can remain strong while engaging in the arts, technology, science and more.

J.M.L.

May 2015